Healthy Calf Conference

Follow to stay up-to-date on all Healthy Calf Conference updates. Speaker announcements, sponsorship information, registration announcements, and more.

By Hannah McCarthy, Ph.D. student, University of Guelph

The preweaning period is one of the most critical phases in a dairy cow’s life. Not only does it carry the highest risk, with the average mortality between 5 and 10 per cent on Canadian dairy farms, but it can also influence the animal’s long-term development and productivity. Preweaning health and nutrition can affect postweaning growth and health, age at first calving, first lactation yield, lifetime yield, and lifetime profitability.

Numerous studies have shown that colostrum is one of the most important factors in determining preweaning health. Calves are born with a naïve immune system and have low levels of circulating immunoglobulins in their bloodstream making them highly susceptible to disease. They acquire immunoglobulins, primarily immunoglobulin G (IgG), via the colostrum provided by the dam or a colostrum replacer. These immunoglobulins provide the calf with passive immunity for the first few weeks of life, until they begin producing IgG of their own.

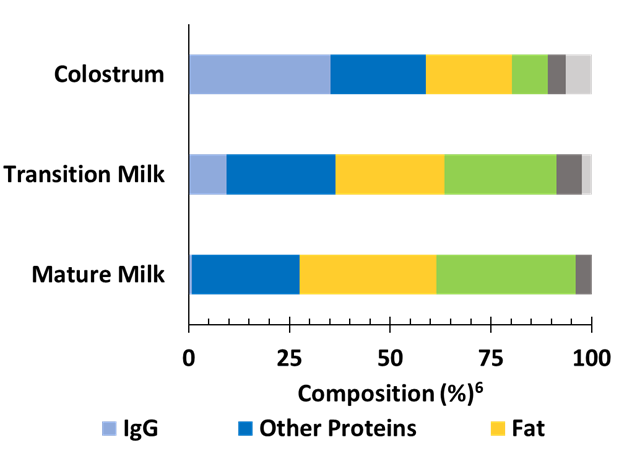

Colostral IgG is only effectively absorbed into the bloodstream of the calf until 24 to 36 hours of life. However, colostrum contains more than just IgG. It contains various other bioactive compounds such as growth factors, immune cells, and bioactive peptides. The first milking after calving contains the highest concentration of these components, but their levels remain elevated until about the sixth milking. This period produces what is referred to as “transition milk,” typically from the second to sixth milking post-calving.

Traditionally, dairy calves are fed one or two meals of colostrum, and the transition milk is discarded. However, in a more traditional rearing system where the calf is reared by the dam, the calf would naturally be consuming the transition milk. As the roles and absorption of many non-IgG bioactive compounds are not fully understood, transition milk may benefit the calf.

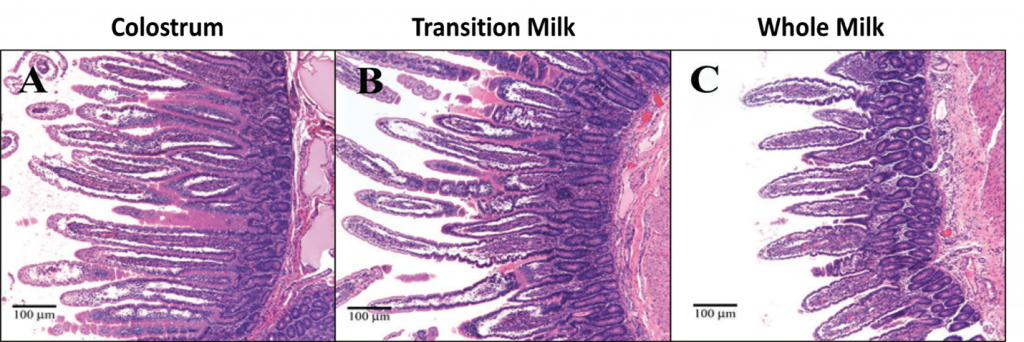

In one study out of the University of Alberta, calves were fed either colostrum, milk, or transition milk from 12 to 72 hours of life, following an initial colostrum meal at birth. Calves that received the transition milk had higher serum IgG concentrations than those calves fed whole milk, though colostrum-fed calves had the highest concentrations overall. Additionally, both transition milk and colostrum-fed calves had increased intestinal development by day three of life, compared to the milk-fed calves.

Another study out of the University of Guelph examined the effects of four diets on preweaning growth and health: 1) milk, 2) transition milk, 3) extended colostrum (10 per cent colostrum, 90 per cent milk), and 4) transition milk, followed by extended colostrum. While there was no effect of the diets on growth, calves receiving either transition milk or extended colostrum had a lower hazard of diarrhea in the first three weeks of life and a reduced hazard of preweaning mortality. Other studies have also observed decreases in preweaning pneumonia rates and improved weight gain using similar feeding strategies.

An emerging area of research involves using colostrum or transition milk therapeutically during stressful periods. One study out of the University of Guelph assessed the effects of feeding a 50 per cent milk and 50 per cent colostrum mixture during an episode of diarrhea. Calves fed this mixture for four days recovered more quickly from the diarrhea. Interestingly, they also found that the colostrum treatment increased preweaning average daily gain, even though the colostrum was only fed for a short period of time. Another study from the University of Guelph provided a 25 per cent colostrum and 75 per cent milk mix once daily during a one-week weaning period. This supplementation improved average daily gain during the weaning week (week nine) and continued to have positive effects on gain into the postweaning period (weeks 11 and 12).

The mechanisms behind these benefits are still not fully understood. Some researchers attribute the effects to the additional fat and energy provided in colostrum. However, even in studies that control for energy and fat content, positive health outcomes have been observed. A prevailing theory is that bioactive compounds beyond IgG may still be absorbed or exert local effects on the calf’s gut. Although further research is needed to clarify the mechanisms behind the observed benefits and to optimize feeding protocols, the existing evidence strongly suggests that colostrum has benefits that extend well beyond the immediate postnatal period.

Follow to stay up-to-date on all Healthy Calf Conference updates. Speaker announcements, sponsorship information, registration announcements, and more.

The Codes of Practice are nationally developed guidelines for the care and handling of farm animals. They serve as our national understanding of animal care requirements and recommended practices.